Exhibitions

Aurora

Solar winds and magnetospheric plasma. Sepulchral lights dancing in the sky. One is from a textbook, the other evokes magic, and both are descriptions of the eerie fragile beauty born out of violence that smears the night sky around Earth's poles. So too with a newly opened sound sculpture at Nuna, Aurora by Lorin Tone—a beautiful mesmeric meditation, an elergy, a calm that addresses a storm.

The sound source for this work—a composition by renowned film composer Hans Zimmer, was written to raise funds for the victims of the 2012 Aurora, Colorado shooting massacre. Twelve people were killed in the shooting and 58 more were wounded by gunfire.

Sound media artist Lorin Tone approached Zimmer's management to gain permission to reinterpret the piece into an interactive virtual sound sculpture. Permission was duly granted and Tone set about deconstructing the work, cutting it into pieces and stitching them into randomised layers, adding silences, superimposing fragments and adding interactive elements.

The result is more than interesting. In many ways it transcends its source material, exploiting aspects of the Virtual Reality medium in ways that are not normally possible in a scored composition. Tone has set a number of speakers in motion to create a ‘sound field’—sound that is constantly shifting in relation to the listener's position. A number of these speakers are activated by touch. The avatars of listeners are able to insert new sonic threads by activating a randomised selection of samples of tuned choral singing. Interaction with the work constantly changes its texture and produces new sonic mixings.

In electroacoustic works of this sort, the sound often moves through a bank of surrounding speakers to produce an illusion of movement—referred to as stereo imaging—and in live performance musicians can play while moving around the audience. But Virtual Reality allows the possibility of moving speakers and a level of personal interaction with the music not really possible in concert halls. What this work brings to its audience is an innovation—a harnessing of the unique potential of Virtual Reality to deliver something artistically 'other'.

Tone has utilised this potential to dramatic effect. This is a beautiful, timeless work, one that weaves magic across spinning stars.

WHERE :Nuna Satellite Gallery: Aurora

WHEN :Now

Exhibitions

Sonic Ocean

The room is white. On one wall sits a large white canvas in three pieces. It has part of a chair etched onto its upper left region. Sparse minimalism, a pale shadow on eggshell white on gallery white, the Japanese quest for poetic subtlety akin to a white bird on the snowy slopes of Mt Fuji. A hand-made chair sits in the middle of the room facing the canvas. It is the same chair that is scratched onto its surface with simple lines, as a child might draw a chair but with more surety.

The chair and the canvas depicting the chair set up an unexpected dialogue between the viewer and the viewed. The chair is positioned to view a painting of itself. It "sits in" for a human viewer. The painting creates a feedback loop, a commentary on the chair and the space that surrounds it.

Where the collective visual space is a meditation on whiteness, the aural space is filled with carefully crafted sounds that connect to the assembled objects along another plane. These are the sounds of the chair being made, the artist in his studio sharpening saws, drawing his plane along wood, speaking to himself as he works. The making of the artwork becomes the essence of the artwork. Sea of Serendipity is a collaborative sound sculpture by Kazu Nakagawa (visual artist), Helen Bowater (composer) and David Bowater (composer/sound engineer). It confronts our understanding of how we perceive art; what limits we assign to an artwork and whether they are real edges or edges that we impose—our own limitations.

The collection of sounds emanating from opposing speakers were recorded in Nakagawa's studio by Bowater and Bowater and arranged into electroacoustic pieces so that, coupled with canvas and chair, the work centres on the hidden relationship between making and viewing art. The compositions, one by each of the Bowaters, are played against each other and they overlay in aperiodic fashion. The overall sound fabric only repeats after a few days so that a dimension of time is added to an otherwise static display.

The Japanese concept of “ma” which Nakagawa employs in his art practice, and which the Bowaters’ echo in this sonic fabric, is at the heart of the work. Japanese design aesthetics place equal or even greater weight on negative space, the space that surrounds an object and is reflected off the object. Ma holds a work in tension with, and extends its reach into, its surroundings. In this work the silences in the sonic textures and the spaces between visual objects are as vital as the objects themselves. Every facet of this work has something to say. It reveals itself to you in "Aha!" moments.

Sea of Serendipity is a thought piece. Its objects almost don't matter—they're like the spectacles you see through rather than the eyes you see with. The chair is skeletal in its rendering, which feels right as the empty/not empty gallery—and what any gallery represents—provides the real flesh for these bones.

WHERE :Nuna Gallery: Sea of Serendipity

WHEN :Now

Exhibitions

Mapping Bodies

Intimate Topographies is an exhibition of new works by Nuna's curator, and resident artist, Alia, at the Nuna Penthouse. In this series the artist takes a cartographical approach to her nude studies. The figures are in close-up—an outline of a hip or a shoulder, a shadow cast by breast or abdomen. The landscape-esque overlay is abstacted—roughened earthen textures to create a beach, or crayon scratchings evoking wind swept grasses.

Contrasts are as important in these paintings as the titled theme which points to 'body as landscape' (rather than 'body in landscape'). On large canvases, broad brush strokes—which have a hasty restless energy—are reworked by subtle shadings of airbrush, careful splatterings and deft crayon scribblings. Colours contrast too, vibrant matched with vibrant, or pastelline against itself. Some hues push into fluorescence and contrast all the more jarringly, especially in the multimedia works. But the most striking contrast is in the subject matter, an unvarnished eroticism tempered with scratched earth or encrusted brine. These works are a meditation on opposites, an integration of yin and yang with blurred edges.

"When I stand behind my easel, I approach something like Plato's World of Forms. The body I'm studying becomes neutered, the sensual and other layered features fall away, but it gains a sort of objective purity. It becomes, for me, a problem of light and shadow. Of texture and grain. I literally perceive the nude as a type of landscape or still life. When I step away from the canvas the nude becomes naked again. A human... of course the model doesn't lose those qualities just because I'm sketching or painting him or her, their intrinsic sensuality is still there in the rendering too, but my perception of them is affected by the act of interpreting them. This series of works is a sort of annotation on that perceptual shift."

The artist has also created mixed media works—time-lapsed morphologies where superimposed layers are revealed fleetingly or an image passes through colour shifts—a psychadelic Warhol of cryptic Marilyns. The whole back wall of the gallery is occupied by a giant curved cinema screen playing a slowly evolving work Riddle of the Sphynx. On this canvas no attempt is made to bury the prone figure in its textural nest, it literally is the smooth sand dunes. The Egyptian Sphynx is imposed in the left corner, echoed by a small replica statue placed in the foreground. The sonic component of the work, by composer Mike Ratledge, makes reference to the Greek Sphynx in its intriguing narration.

The Sphynx in this artwork is the female principle, capricious as the femme fatale riddler who devours those that cannot solve her riddle. She is the ancient goddess, an erotic invitation to bind with the fertile Earth in her prone form. And she is the voice that speaks exclusively to women as they come to terms with their bodies, attracted and repulsed by their fertility. Intimate Topographies might be read as an artist's self-portrait in quantised portions. But the commentary goes beyond that, delving into what it means to be who you are. A japanese waka by Ono no Komachi accompanies the painting Intertidal I: Ocean—a stark portrait of the artist's pelvis. Ono no Komachi was one of the great woman poets of the Man'yōshū from the early Heian period and a legendary beauty. It reads:

Doesn't he realise

that I am not the swaying kelp

where the seaweed gatherer

can come as often as he wants

WHERE : Nuna Penthouse Gallery 1

WHEN : Now

Origins Series

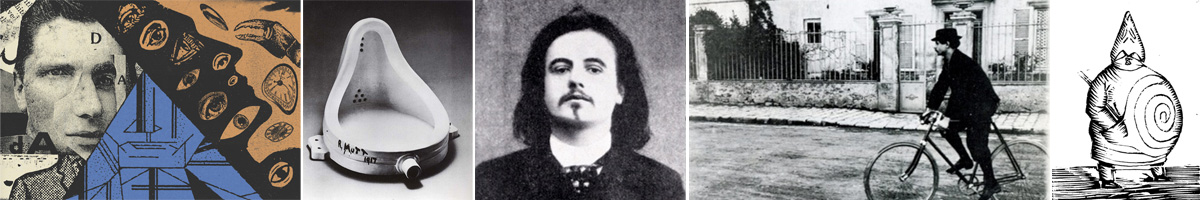

Dada

Dada was the first conceptual art movement where the focus of the artists was not on crafting aesthetically pleasing objects but on making works that upended bourgeois sensibilities and that generated difficult questions about society, the role of the artist, and the purpose of art. It arose as a reaction to World War I and the nationalism that many thought had led to the war.

Dada embraced absurdity and dadaists were so intent on opposing all norms of bourgeois culture that the group was barely in favour of itself, stating "Dada is anti-Dada". Leading artists associated with it include Arp, Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia and Kurt Schwitters. Duchamp’s questioning of the fundamentals of Western art had a profoud subsequent influence on its development.

In this article tracing the origins of Dada, I'm going to take you on a Dada-esque journey. It starts in the 1890s with a diminutive Parisian, Alfred Jarry, who invented 'Pataphysics—the supremely ironic meta-metaphysics. This brief biography of Jarry is told with a nod or two to pataphor. A pataphor (Jarry's creation) is an extended metaphor that creates its own context (that which occurs when a lizard's tail has grown so long it breaks off and grows a new lizard!). All details of this history are accurate to the extent that any historical writing can be labelled accurate (i.e. not a work of fiction to the best knowledge of the author). At the end I'll supply a glossary of pataphysical terms to help you make sense of what you just read :)

The Copper Skiff: A Pataphysical Introduction to ‘Pataphysics

Alfred Jarry rode around the streets of Paris on a bicycle, his means of locomotion, carrying a green umbrella and two pistols. The pistols he fired to announce his arrival. His style was unique and remained so until Pablo Picasso, an admirer, acquired a pistol of Jarry’s for his own nocturnal peregrinations of Montmartre, where by day he was known at the Lapin Agile for buying his meals with a drawing. “Why don’t you ever sign your drawings Pablo?” asked the owner. “Because I only want to buy lunch, not your whole restaurant!”

Jarry, from the formative age of 17, had been a regular presence in the cafés of the Latin Quarter across the Seine, which snakes around the Ile de la Cité with a somnolent glide; hissing on masonry and slithering past the footings of the Pont au Double, its reflected lights a backdrop for the waiter whistling as a bar on Quai de Montebello approaches closing time. He notices a man of diminutive stature drinking from his own absinthe bottle at a street table and decides not to disturb him. It is Jarry returning from a play. In those cafés Jarry mingled with artists, philosophers and writers including a few Symbolists. Their theatrical productions were being noticed in the 1890s. Symbolism had pushed away from the Realism and Naturalism that were then the mainstays of French theatre. Authors like Stéphane Mallarmé, who befriended and mentored Jarry, and Alfred Vallette were choosing metaphysical poetry over stilted realism.

Jarry was excited by this stylistic revolution. He adapted their influence to create his own absurdist style of writing and, out of his inventions, Jarry did more than just create absurd characters—he adopted their mannerisms as his own. To a neighbour's obnoxious (or reasonable) complaint that Jarry’s pistols endangered her brood, he quipped, "If that should ever happen, ma-da-me, we should ourselves be happy to get new ones with you."

That talking style, the royal “we”, “ma-da-me”, announcing each syllable with nasal relish as though it were a new word, he acquired from Pere Ubu, the redoubtable King of Poland, who cut his own three teeth—one stone, one iron, one wood—teaching physics to Jarry under the pseudonym Felix Hébert. Imitating the speaking style of his teacher, who Jarry caricatured as a buffoon, completed the circle for Jarry. To adopt his speaking mannerisms, which were exaggerations of his own anyway and perhaps not Hébert’s at all, defied any reasonable explanation, and that was what counted. The mannerisms were really a form of symbolism, a metaphor for the teacher; by adopting them Jarry was growing a new lizard out of the abandoned tail.

In Ubu Roi, which premiered on 10 December 1896 at the Théâtre de l’OEuvre—a play that pre-empted the wonderful Theatre Absurd—the comically obese Ubu stepped onto the stage and announced “Merdre!” (a clinamen of Merde); its resemblance to the degenerate substance still close enough in French to create chaos in the audience. The booing, whistling and jeering lasted a full 15 minutes as an antimonious posse of depraved miscreants baited, cheered and applauded. Opening night was also closing night. Lugné-Poe, the theatre’s manager, shut down the play immediately due to the heat of the scandal and the rioting of the patrons, but Jarry had become famous literally overnight.

Spurred on by the success of this venture, Jarry refined his talking style further: his bicycle became ‘that which rolls”; the wind, “that which blows” and he always thereafter referred to himself with the collective noun, the absurdity of doing so dovetailing nicely with his other self-conscious eccentricities, much like the dovetailed jointing on the cabinet where he kept his revolvers, in a room too low-studded for anyone but Jarry to remain erect. Visitors crouching to shuffle around created a slapstick reality, which Jarry likely viewed as a syzygy of sorts. All this chaos was on account of his landlord’s anomalous caprice—dividing a larger apartment into two by way of a horizontal partition instead of the more sensible vertical. It should be a rule that every budding pataphysician inhabits an absurdity generator like that one to really get a feel for the subject matter.

Keenly aware that he cut no less comical a figure for his lack of elevation than the well-meaning Hébert did for his excess of girth, Jarry—in the modern coinage—chose to monetise his gift. He had already achieved dismissal from the army, into which he was drafted, by marching in a uniform too large for his stature, making a parodie of parades, another clinamen. They found medical grounds for his dismissal. The oversized uniform became one of his motifs, worn by the oversized Pere Ubu, no less, with whom, as mentioned, he had very little and a great deal in common. He wrote a set of plays featuring the vulgar Ubu, finding scant profit as he tried to reconcile the need for the involvement of the spectator with his “didactic misanthropy.” He both mimicked and mocked the Symbolists—and with that innovation his unique formula propelled theatre into a tango with absurdism, art towards Dada and scholarship into the age of post modernism. Not bad for a wee man on a bicycle.

While five novels and two collections of short stories were published during his lifetime, Jarry’s influence on the 20th century did not properly manifest until after his premature death from tuberculosis abetted by substance abuse—he squandered his modest inheritance developing a taste for libations and taking ether when he could not afford la fée verte. Exploits and Opinions of Dr. Faustroll, Pataphysician, the surreal work that launched Pataphysics on the sea that sits over Paris; and La Dragonne, were both published posthumously. Dr Faustroll died the year he was born at the age of 68. Jarry died in 1907 before he was born, his philosophical system of Pataphysics a posthumous love letter to the world, sealed in an absinth bottle, floating away from a copper skiff on the shimmering absolute, a golden sea above the city of lights.

Pataphysical Glossary

Clinamen: a swerve of atoms

Syzygy: an unexpected alignment

Antimony: a symmetry of opposites

Anomaly: an exception that disproves the rule

Absolute: a transcendent reality

Pataphor: a metaphor’s metareality

Source Material

Alastair Brotchie, Alfred Jarry: A Pataphysical Life. 2011

Maurice Marc LaBelle. Alfred Jarry, Nihilism and the Theater of the Absurd. 1980.

Martin Puchner. “Alfred Jarry.” The Norton Anthology of Drama. Vol. 2. 2009.

Origins Series

Theatre of the Absurd

Flashback to an age of innocence: my days as an art student. I whooped with delight when I delved into Dada. It made perfect sense! The world, I had been taught, is built on truths—we just have to find them and everything will be better. Everything will make sense. Progress equals happiness. Yay for the atom… yay for the dishwasher…

Except of course it doesn’t and it will probably never make sense. Dada artists rejected the logic, reason, and aestheticism of modern society. They stood beside the ruins of the Great War and saw no logic, no sense. Dada manifested their vision in nonsense, irrationality and anti-bourgeois sentiment. “I see your stupidity and raise you,” they said. “There is only nonsense,” they said.

I was ready to sign up on the spot. I’d stumbled on an idea that had been brewing in my own mind since childhood, albeit without a name. And now it had one! But I was too late! It turned out that Dada had long ago evaporated into Surrealism, Pop Art, and then poof, gone! My spiritual home was an overlooked casualty of WWII. My path was closed. I would have to join my Derrida-toting peers and embrace um… Post-Post-Deconstructionism? …Meh!

Until, wobbling recklessly into my pit of despair, came a new light.

Flashback (much further) to 1893. A play, Guignol by the diminutive Parisian, Alfred Jarry, had included a reference to ‘Pataphysics. A shot had been fired at the void. There was smoke in the air.

Jarry derived the name ‘Pataphysics from the Greek, τὰ ἐπὶ τὰ μεταφυσικά (tà epì tà metàphusiká): that which is above metaphysics, and it most likely began its life as a wry joke, a parody on Aristotle’s Metaphysics. But, like wry jokes sometimes do, it resonated for Jarry. He fleshed out the idea in his delightful novel, Exploits and Opinions of Dr. Faustroll, Pataphysician.

The novel relates the adventures of Dr. Faustroll (a scientist who is born in 1898 at the age of 63, and who dies the same year at the same age) and his companion, a lawyer named Panmuphle, on their travels in a copper skiff on a sea that is superimposed over the streets and buildings of Paris. Written in the first person by Panmuphle, the narrative describes the fantastic islands that they visit. The pair are accompanied by a monkey named Bosse-de-Nage, who perishes along the way, leaving Panmuphle wondering if he had imagined him or whether he had been real.

At the end of the novel Dr. Faustroll dies, and he sends a telepathic letter to Lord Kelvin describing the afterlife and the cosmos. The symbolism of the novel has imagination and language overriding the reality of the French capital, and the story is wryly comic and surrealistic in nature. The novel concludes with the line: "La 'Pataphysique est la science...

Just so!

Jarry, it turns out, had been a major inspiration for Dada. Their vehicle of protest may have sprinted ahead and run out of gas but Jarry’s ‘Pataphysics was still idling in first gear.

The online dictionary defines ‘Pataphysics as:

a supposed branch of philosophy or science that studies imaginary phenomena beyond the realm of metaphysics: the science of imaginary solutions.

Supposed! How unkind! The College (founded in 1948, four decades after Jarry’s death) describes itself as: "The vastest and most profound of Sciences, that which indeed contains all the others within itself whether they want it or not."

Thank goodness for balance! Jarry, unknowingly, had laid the groundwork for Le Collège de 'Pataphysique. They picked up the baton.

’Pataphysics, science of the particular, science of exceptions (it being clearly understood of course, that the world contains nothing except exceptions, and that a “rule” is precisely an exception to the exception; as for the universe, Faustroll defined it as “that which is the exception to oneself”.

The Science, to which Jarry dedicated his life, is practised unwittingly by all mankind. Human beings could more easily dispense with breathing than with Pataphysics. We find ’Pataphysics in the Exact and Inexact Sciences (though nobody admits it), in the Fine Arts and the Foul Arts, in every kind of Literary Activity. Open the newspaper, turn on the radio or television, explore the Internet, speak : 'Pataphysics!

’Pataphysics is the very substance of this world.

Aside from my love of subversiveness—which in ‘Pataphysics rolls out like thunder on the horizon, beyond which a wagon stops by a river to refresh the horses where the wagoner discovers his grey gelding needs a shoe—what really got me hooked on ‘Pataphysics was the “pataphor”. It is the juiciest of literary morsels. A pataphor is an extended metaphor that creates its own context (that which occurs when a lizard's tail has grown so long it breaks off and grows a new lizard!).

Jarry stated that 'pataphysics existed "as far from metaphysics as metaphysics extends from regular reality," therefore a pataphor is a figure of speech that exists as far from metaphor as metaphor exists from non-figurative language.

An example from Pataphor Test, by Pablo Lopez:

"Jenny is eleven years old. She lives on a farm in Luxembourg, West Virginia. Today Jenny is collecting eggs from the hen house. It is 10 a.m. She walks slowly down the rows of cages, feeling around carefully for eggs tucked beneath clucking hens. She finds the first egg in number 6. When she holds it to the light she sees it is the deep tan of boot leather, an old oil-rubbed cowboy boot, creased with microscopic branching lines, catching the light at the swelling above the scarred dusty heel, curled at the cuff, bending and creaking as the foot of the cowboy squirms to rediscover its fit, a leathery thumb and index prying at the scruff, the heel stomping the floor. Victor the hotel manager swings open the door and gives Cowboy a faint smile."

Non-figurative—Jenny is in reality.

Metaphor—The boot is in metaphor.

Pataphor—Cowboy, the hotel, Victor, exist in pataphor.

Lopez goes so far as to see parallels with QM saying concepts like String Theory constitute a kind of mathematical pataphor. These concepts mirror the 'pataphysical idea of "supposition built on supposition." String Theory is speculation based on ideas that are ''themselves speculative'' (the theories of General Relativity and Quantum Mechanics), therefore String Theory is not in fact physics, but 'pataphysics.

Joy!

Terracotta Warriors

Army of Individuals

The vast number of terracotta sculptures buried with the self-declared First Emperor of the Qin dynasty (Qin Shi Huangdi) were intended to protect the deceased emperor in the afterlife and announce his importance and power on arrival. They have instead become a standing testimony to the artistic talents and craftsmanship of the Chinese 200 years before the beginning of the common era, in much the same way that the pyramids have conveyed the incredible talents and ingenuity of the ancient Egyptians ahead of the significance of the Pharaohs. They reveal an artistry no less dazzling than that of their classical European counterparts, an eastern classicism to parallel the art of Greece and Rome.

There’s the armoured general, his face etched with experience. The lines stand out on his forehand and you can count the strands of hair in his beard. His broad shoulders, paunch and strong legs match the authority of his face and in his stance. A horse stands alert: its ears pricked forward, nostrils flared, ready for action. Then there’s the archer, captured in the moment after he has released his bow. His eyes follow the arrow’s trajectory. Legs parted, chin slightly raised, shoulders drawn back, he is the epitome of grace and elegance. Each piece makes a statement completely at odds with what we now think of as mass production.

The roughly 10,000 life-sized sculptures were designed and sculpted individually, each with its own face, hair, clothing, weaponry (real weapons added to the sculptures) and personality. These unique features were added onto base frames that were constructed in methods resembling modern assembly line production. The sculptures were originally brightly painted, augmenting their individual character, but sadly the colours have not survived exhumation from the necropolis surrounding the tomb site. The lacquer covering the paint can curl in just fifteen seconds once exposed to Xi'an's dry air and flakes off in less than five minutes. We can only imagine the riot of colour that must have been.

While the emperor's legacy may be in serious doubt—his ability to marshal people to work on enormous projects like his mausoleum notwithstanding—that of the designers and artisans of the terracota sculptures still being uncovered today is not. An "army" of roughly 7000 labourers and artisans combined to create these figures. During his rule, the emperor's generals united much of modern China and ended over 200 years of wars between competing states (referred to as the Warring States period). He brought the combined region into a single administrative system to ensure a common experience across the entire region, including standardising weights and measures. He built new roads and also destroyed many existing internal walls that had been constructed to protect one state from another. These are all laudable achievements.

But they are heavily outweighed by his legacy as a tyrant and a madman (the latter perhaps a symptom of his persistent attempts to extend his life with alchemy).

In an attempt to standardise people's thinking he banned Confucianism and other schools of philosophy, ending a golden age of free thought. He ordered the burning of most books, denying future generations of the wisdom and philosophy of past generations. He replaced the internal walls with a unified barrier on the northern border in an attempt to dissuade "barbarian" raids, which would eventually become what we know today as the Great Wall of China. The project came at an enormous cost in human life (some estimates put the number as high as one million deaths) and lost productivity, but produced only dubious benefits.

Trade with the outsiders was an important part of the border economy, the border gates remained open and people on the border were often friendlier with the outsiders than they were with the central government. Eventually the "barbarians" successfully invaded the country and ruled it for nearly 100 years. The emperor's support and advancement of a political philosophy similar to modern Fascism led quickly to resentment across the country, stifling of innovation and creativity, and many assassination and coup attempts. As a direct result and despite claims that he was creating a great dynasty that would last thousands of years, the Qin dynasty was overthrown after less than 15 years in power, ushering in the 400+-year -long Han dynasty and a period of philosophical revitalisation and rebirth.

Within the mausoleum, the sculptures were carefully placed in formations to match military strategy. One can clearly make out the application of Sun Zi's (Master Sun) advice to armies, passed on to current generations in The Art of War, which is believed to predate the sculptures by several centuries. He advocated for a hard offensive edge backed up by a strong defence. Following that strategy, one finds in the first pit of sculptures three rows of archers, used to make the first offensive attack. But immediately behind them are 11 solid rows of fully armoured warriors, prepared to step forward and take on incoming forces and to protect the first line. These soldiers are joined by horse-drawn chariots ready to penetrate deep into enemy ranks to find their weak spots. The horses have been designed and sculptured to portray powerful and majestic animals.

The second pit is arranged similarly, with crossbowmen out front, arranged in staggering formation to allow for a continuous flow of arrows despite long loading times, and a large contingent of armoured chariots and single-rider cavalry. Additional chariots are placed to allow commanders to get directly into the field of battle. The third pit represents the command post. If it weren't buried, one could easily imagine the intent was to both celebrate successful military strategy and provide a model to future armies.

Other pits provide a glimpse into aspects of life (or afterlife) in China. There are scholars and clerks with tablets for writing, and even a group of terracotta acrobats to entertain the emperor. Experts have suggested these acrobats represent a sharing of cultures between China and the cultures south of China, from modern-day Burma.

One gets the sense, looking at the sculptures, that the artists were engaged in a tacit rebellion. Where the emperor intended these pieces as a celebration of his greatness, they portray instead a celebration of individuals in their diversity. A modern commander-in-chief looks at soldiers as interchangeable, but these artists took special effort to make clear that each person is portrayed as an individual, serving their role. Every role is carefully studied and presented, no one elevated above another (excluding the obligatory exalted space left for the emperor to occupy).

The emperor's poor reputation after his death led to attacks on his mausoleum that damaged and destroyed many of the sculptures. Whole pits were set aflame in protest at the end of tyrannical rule. But a large army of warriors survived, preserved in the earth, and were lost to antiquity until their 1974 rediscovery. Where the emperor’s tyranny and hubris have now faded with him into historical footnotes, the art he commissioned has emerged as an expression of human creativity, thought and ingenuity.

Identity

Virtual Quandry

There are two computer generated humans on my screen. They are talking. I know because I can read their conversation. One is a nondescript male in nondescript clothes. He doesn’t move much except to turn in the direction of whatever he’s looking at. And right now he appears to be looking at the woman, or through her, into space (one of his many bad habits). She is attractive and somewhat more animated than he. Her gestures and movements are realistic. Her clothes are tailored. Nice hair too. Nice everything. I’m the nondescript one, he’s my avatar, Mr Brick-In-The-Wall. He moves for me when I play with the arrow keys on my keyboard.

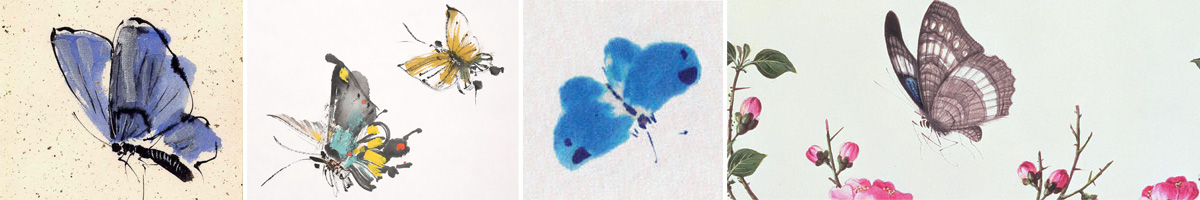

We avatar owners live on opposite sides of the world but right now we are both standing in the same room. Talking. We could be conversing via an online forum, via social media or in a Google hangout, as many people do of course, rather than standing in a room in our simulated bodies, but this way of chatting is a lot more immersive—oddly, more human too because there are visual cues. We’re both experiencing the same environment and that informs our discussion. The environment on this occasion is an art gallery, Nuna, in 3rd Rock Grid. I am able, in my avatar body, to walk around this gallery, to sit on a seat in front of a Botticelli for a few minutes to take it in. I can wander over to a lift and go to the next floor, pad around absorbing displays of traditional Chinese art and Maori Te Moko tattoo. Or, if i want to get away from restrictive terrestrial rules, I can hover like a butterfly as I move around the gallery.

Speaking of butterflies… a famous Daoist parable goes like this:

"Once upon a time, I, Zhuangzi, dreamt I was a butterfly, fluttering hither and thither, to all intents and purposes a butterfly. I was conscious only of my happiness as a butterfly, unaware that I was Zhuangzi. Soon I awakened, and there I was, veritably myself again. Now I do not know whether I was then a man dreaming I was a butterfly, or whether I am now a butterfly, dreaming I am a man...”

Zhuangzi was asking how we know, when we experience waking up from a sleep, that it is a waking up to “reality” as opposed to merely waking up into another level of dream?

This may not be the philosophical dilemma you take with you to bed every night, but questions of identity do arise when you spend a bit of time pushing an avatar around. These avatars have a nasty habit of developing their own personalities… similar to yours, but different too. It gets quite complex. This isn’t just a game—in fact this style of immersive VR isn’t a game at all. There is no goal, task or quest involved, as you would have in a proper game—you simply join a community of avatars and get on with your virtual existence. Some people even seem to prefer their virtual existence—perhaps their avatar has more control over the fates, or a better social life. Virtual reality provides a real-time, immersive social space for people with physical or mental disabilities that impair their first lives, who often find comfort and security interacting through anonymous avatars.

Approaches vary wildly on how people prefer to be represented virtually. Some (like me) prefer as-close-to-real-life-as-possible given the available options. I once chose a monkey because it felt more like me than any of the human avatars available in that particular virtual reality. At the further extreme some people prefer to immerse in VR as mythical beings, but these are relatively rare and typically involve extra expense or (for those with the talent) a fair amount of design effort.

Most people choose or create something that represents an aspect of their identity which then grows into their avatar. A surprising number of men choose female avatars, whereas very few women appear to choose male avatars. For this reason alone, Carl Jung would have been delighted with virtual reality. In his theory of the collective unconscious, Jung believed the anima makes up the unconscious feminine qualities that a man possesses, and animus the masculine ones of a woman. We are accordingly the sum of our conscious and unconscious minds in tension. He believed that the anima and animus manifest themselves in dreams and influence a person's attitudes and interactions with the opposite sex. It follows that because men repress their sensitivity (their inner feminine aspect), anima is a stronger personification of their unconscious. In Jungian terms, perhaps a gender selection bias is entirely predictable, nature balancing itself within the human breast!

Gender swapping aside, an interesting thought experiment is to ask yourself how—given the power—you would have designed the “real” you differently to the one built from your genetic code. Would the designed you be smarter? Better looking? Healthier? Imagine we all have that power. Would we design ourselves as clones of each other according to modern aesthetic preferences: all of us intelligent and talented, tall with the same blemish-free skin and thick healthy hair, same movie star features and rippling physiques? A scan of typical avatars suggests many of us would. Diversity in virtual reality is more extreme but less common. Individuality is not something we really aspire to, it would seem—big ears and a crooked smile are vastly less popular than six-pack abdominals.

But, as noted above, some people invest heavily in their virtual life and the questions that arise about which you is the real you become more vivid for them. Putting it another way, which iteration of you conveys your essential nature more accurately and provides better self-actualisation? The one you accept with all its flaws and drive through your managed life in “reality”; or the one you create personally and drive in the unchartered space of virtual reality? Arguments can be made for either position. Identity, your identity, is the stake you play with when you enter an immersive virtual world. Some lose it in the transaction and become the butterfly they dreamed. Others simply gain a new butterfly.

Pride and Prejudice

Disconnect

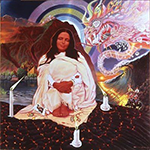

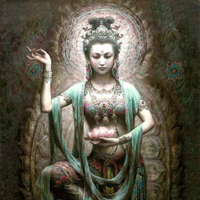

The images that tease you into this brief essay are by an artist you've never heard of, but you probably know his work. Abdul Mati Klarwein.

His artistic pedigree was immaculate. In the 1950s he went to Paris and studied painting with Fernand Léger. In St Tropez he received private tutelege from Ernst Fuchs. In New York Andy Warhol stated that Mati Klarwein was his "favourite painter". Mati Klarwein rubbed shoulders with the rich and famous. He dropped acid with Jimi Hendrix. He was commissioned to create new works for Jackie Kennedy, David Niven, Brigitte Bardot, Richard Gere, Leonard Bernstein and Michael Douglas, to name but a few. He was that rare thing, a celebrity among celebrities.

Where you may have seen his work though, is in connection with music. His paintings adorn seminal album covers from the 60s and 70s. He painted The Annunciation which is the cover of Santana's Abraxas. His works were used for the covers of Miles Davis' Bitches Brew and Live Evil albums. Musicians from that era clamoured for his art.

Despite all this attention, or perhaps because of it, his name doesn't appear in any history of 20th century art. He never worked with galleries or used any conventional forum within the well-defined boundaries of the world of art. He still remains (posthumously) shut out from the art establishment, unworthy of art criticism. This is not because he lacked originality as an artist. Long before Banksy developed his legendary distain for conventional practice, creating works and just leaving them randomly for others to profit from, Mati Klarwein had cultivated his own measured distain for his art product. He maintained the image was important and would happily paint replicas of his pieces if requested. He did not trouble himself to know what happened to any of the original work on completion. And like his admirer Warhol, Mati Klarwein accepted no boundary between his own work and the work of others, often buying paintings and working on them himself, unfussed if the same treatment befell his own paintings.

Nor was he a stranger to controversy (normally a catapult into the collective arts consciousness). In New York in 1964 he caused a commotion exhibiting his blasphemous Crucifixion. The painting depicts people cavorting in a garden of earthly delights where no sexual, racial or gender barriers exist. Public outrage to this work was such that he was even attacked by a man with an axe.

But, out of his broad spectrum of themes, his multi-ethnic, trippy, psychedelic musings did spark the imagination of an era of musicians who were experimenting with these same influences. And being popular with the wrong audience is something of a no-no in the serious world of art, a logic that aligns with the refrain "my enemy's friend is my enemy". In this case, the public, the “Great Unwashed” is the enemy. In telling contrast, the enormous enthusiasm within the arts establishment for an outsider like Banksy—a direct heir to the spiritual rebellion of Mati Klarwein—might have something to do with him being their discovery. It's, you know, ok for the public to follow—not so good when they lead. And that is the theme of this little exposition, the double-edged sword of art criticism.

Art criticism performs a vital function for art. It moves works, artists and events from short term to long term memory, etching it on the public record. Art is local and often ephemeral by nature so the critic disseminates the work in publications, books and other written media. They also evaluate art, which is an important function, prising out meaningful ideas in an ever shifting sea of relevance. So to preface my minor criticisms of critics, let me say that it is with an eye to the important role they fill, and against a backdrop of admiration for their craft.

It is a craft that requires passion for the subject matter. In light of this, professional impartiality is an impossible standard to expect or attain. The grasp that a critic has on art history is their best guide when evaluating new work, and the path that art has taken since the revolution of modernism looks from our present perch, necessary, inevitable, making it hard to imagine that other paths might lead anywhere worthwhile; while the paths that stay closest to their starting point (those that put realism and technique on a pedestal) are also the least interesting to the adventurer.

This is central to why hyperrealism has trouble being taken seriously by those who determine historical significance, and so too for Abdul Mati Klarwein, who was something of a pioneer of the movement, a bridge between surrealism and hyperrealism. It's also true that some exponents of the contemporary realism genre are as shallow as their pigments and they don't extend the language of art in any meaningful way, but the same charge can be levelled at many artists in other styles too. Some are astoundingly shallow and opportunistic style-plagiarists, but they avoid stigma by being on the right bus. There is a problem of prejudice at work.

The art establishment can’t afford to hold such a blinkered perspective. It’s fair to say that there are a lot of naive exponents of outsider art movements and a lot of misunderstandings among its practitioners. But outside the cloistered arts system is also where the next revolutionary gem is likely to arise. I point again at Banksy as a case in point.

Inspiration

Disconnect

From Homage to Plagiarism

The composer Jack Body created a corpus of works he labelled ‘transcriptions’. A keen ethnomusicologist, Body made field recordings of ethnic musicians and ensembles throughout Asia: Indian street bands, Indonesian folk singers and food sellers, rural Chinese musicians, Papua New Guinean tribal rituals. He diligently transcribed what he heard for Western ensembles and orchestras, fascinated by the outlandish rhythms and tonalities, the exotic melodies, and many of these compositions were transcribed verbatim, albeit for different musical voices. Body made no secret of his sources. In his lavishly packaged cds the composition/transcription is included with its source recordings. The works’ titles lead you back to his source material. He asks you to listen to both versions.

One or two practitioners in the classical music world got a bit sniffy about Body’s processes, wondering: “but where is the composer, where is the creative spark?” This type of question assigns an all-or-nothing value to the notion that what pours forth from an artist must needs originate wholly and solely in their imagination. Patent nonsense, of course. Isaac Newton put it best when he said of his scientific revelations: “If I have seen further than others, it is because I stood on the shoulders of giants.” Art is a cumulative process.

Wander around Nuna Gallery and you will see art—some of it very famous art—that owes a massive debt of gratitude to its authors' mentors and forebears. Originality is not a mystical process, it happens when the path you’re already on takes an unexpected turn and you have the gumption to follow this new path into unchartered territory. Originality is a mindset, it arises when you trust your instincts and processes; it doesn’t fall out of the sky on the wings of a muse to settle on you if you are the Chosen One, the myth of magical inspiration. Originality resides inside you. It is what makes you You, and not the person in the next chair.

A hot issue in the arts, especially in recently colonised countries, and still far from resolved, is ‘cultural appropriation’. Picasso took inspiration from African tribal masks and Pacific motifs. Matisse and Gauguin took ‘inspiration’ from tribal cultures too. Raphael famously and surreptitiously stole a figure from Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling while that master was still on his scaffolds. Art historian Kenneth Clark opined “The great artist takes what he needs!” Raphael did not hide his theft, his painting can be viewed in the papal suite at the Vatican, a short distance from the Sistine.

So when is stealing someone’s swag homage? When is it inspiration? When is it appropriation? And when is it plagiarism?

An anecdote was related to me by a composer friend. I won’t use identifiers, this is a history better forgotten. In her university composition class some years ago were two talented composition students. Student 1 wrote a piece which I’ll retitle Metamorphosis. It earned him local fame. Student 2 took Metamorphosis as the structure for a work, using every second note and “tweening” with her own note selection to create a different piece. Her work, too, was well received until Student 1 analysed her score and discovered her naughtiness. And here lies the rub. Had student 2 titled her piece Variations on Metamorphosis or Homage to Student 1, drawing attention to its source, the piece would simply have been judged on its merits and accepted as a compliment by Student 1. But she didn’t. She stole his structure without acknowledgement and called it her own. That was the end of her promising composing career and the stigma of theft still attaches to her name. A strange business.

I came across a painting by a leading Woman Artist, Hinetitama by Robyn Kahukiwa, and immediately recognised its source. I’ve been troubled by this discovery for a while. Her painting has become an important statement in the indigenous canon to which she belongs. It graces a book cover, posters and appears in other literature. It has been solemnly analysed and approved.

Here is a quote from a reputable historical reference:

"The interpretation of the women in this series can be seen as a feminist reading of traditional Māori mythology. Kahukiwa attempts to redress the conventional portrayal of women as less important than their male counterparts. Hinetitama is an example of the bicultural style that is common in contemporary Māori art. Traditional subject matter is fused with a Europeanised style. While the figure is strongly representational as is typical in Western art, the symbolism which is an integral part of the work identifies it as Māori.

Symbolism:

Tane is depicted as a stylised tiki superimposed upon the figure of Hinetitama and forming the bones of her arms.

The lizard represents Maui in the disguise he adopted when he tried to triumph over death.

The foetus represents the children of Tane and Hinetitama—the human race.

The spiral is an important element in traditional Māori carving. Here it represents the ten overworlds. The horizontal layers of colour represent the ten underworlds."

But nowhere can I find any mention of homage, inspiration, influence or acknowledgement to its source, not from the artist, and not from the art historians who have reviewed her work and placed it on its pedestal. The source work(s) are by Abdul Mati Klarwein. I’ve written about him here. Klarwein was as an outsider to the arts establishment, so art historians can (only just) be forgiven for being unfamiliar with his work. In the header strip above, Kahukiwa’s work is on the left and Klarwein’s is on the right. Klarwein’s work was published in his widely distributed book ‘God Jokes’ (1977). Kahukiwa’s painting is dated 1980. Note the pose, the bright outline, the male skeletal figure—down-pointing penis and all—superimposed on the female figure. Judge for yourself.

The plagiarism doesn’t stop with this one image of Klarwein’s though. "Original" features of Hinetitama are easily identified as motifs in other works by Klarwein, all from the same publication: the stepped aura and the baby attached by umbilicus. To really complicate this piece of art thievery, it could be contextualised (or apologised) within the context of ‘reverse’ cultural appropriation. Reverse in the sense that this time the indigenous artist has claimed another’s imagery into the sacred lexicon of her own culture. When I pointed out Kahukiwa’s deception to an artist friend, her reaction was: “Fair enough, [Robyn’s] appropriating her own culture back from those who stole it in the first place!”

Except that she isn’t. Klarwein was born of Jewish parents and he grew up in Palestine. The Persian world has not appropriated culture from Polynesia. Nowhere in Klarwein’s paintings or artistic language is there any cultural appropriation from Polynesia. The true irony is that Klarwein would not have minded Kahukiwa’s appropriation of his personal vocabulary, such was his nature. The question though, is, should we mind?

Kahukiwa’s original sin was to appropriate and closely transcribe Klarwein’s imagery without any mention of her obscure source. In some ways an attribution of source would have added richness to her work, a layer of purposefully retooling one culture into another. As her work was warmly received and the accolades poured her way though, she became entrenched in her silence. She painted Hinetitama two decades before the internet came along, in a time when it was very unlikely anyone in the arts establishment would be familiar with Klarwein’s work and with the comfortable knowledge that his book—a lovechild of the 70s—would disappear and be forgotten. But the nature of information and institutional memory has changed. Kahukiwa will be found out. If I have seen this and now you have seen this, so will others.

What is her remedy? What would I do in her shoes (other than not wear them in the first place)?

She should, of course, confess. Confess before exposure, not spin after exposure. She should explain her appropriation, if there is an explanation, apologise if there is not. We are all entitled to mistakes of miscalculation. We should not allow them to become dirty little secrets. Kahukiwa is a talented artist with a body of original work in her portfolio. Yet her legacy could pivot on this one detail. By remaining quiet she raises the question: does a thief only steal once? Questions of that sort can throw your life’s work under the bus.

The difference between homage/inspiration and theft/plagiarism is honesty.

VR

Virtual Reality

Nuna Art Gallery is located in a virtual reality called 3RG (3rd Rock Grid). 3RG is a simulation run out of the Netherlands by a non-profit entity. It is open to the public and free to access from your personal computer anywhere in the world using an avatar. The software that lets you create and customise your avatar is free to download, simple to set up and entry into 3rg is also free. With an avatar you can wander around all five floors of Nuna (catching an elevator between floors) to enjoy a fully immersive art gallery experience.

Nuna is laid out like a regular—albeit extensive—art gallery. Its collection of artworks is displayed by category throughout the main building. The collection includes important art movements and styles beginning with prehistoric and folk art and moving chronologically to the present. Works are captioned and short essays introduce periods and genres. There is a sculpture park at ground level and the gallery is set in park-like surrounds. It also has a gallery shop with free 3d models, posters, books and even some Nuna branded clothing for your avatar.

So how, exactly, does one experience this virtual gallery? What equipment do you need? What knowledge? Do you have to be a virtual gamer or developer to do this? The answers are: you already have the technology if you're reading this article—any modern PC with an internet connection is fine, and no special knowledge or aptitude is required. You need to sign up with 3RG for an avatar where you will be walked through a simple set up. This sign up will also direct you to a free viewer download. You need this viewer to appear "inworld" and to control your avatar.

When you log in for the very first time you will appear in a Welcome landing area. On 3RG this is just outside a large building that has eggs on its roof (don't ask!). Inside the building are treasures. There are tutorials to guide you on how to move and manipulate your avatar, and resources for customising the look of your avator—an array of different avatar sizes, shapes, clothes, skins, eye colours, and animations to customise how your avatar moves.

Think of all this as the loading programme in The Matrix. Your avatar is a virtual extension of your personality and is your property. Naturally you can treat your avatar as a simple vehicle to explore virtual space but you will meet and talk to other avatars wandering around this environment and there is something in the human psyche that generally asserts a principle of individuality over generica. The resources in Welcome and tools in your viewer allow you to customise your appearance without limit.

The next step is finding your way to Nuna. The Welcome centre can help you here too. Avatars teleport from region to region and at the welcome centre you'll see signs advertising Nuna—touch one of these signs with a right click to magically appear at the gallery. If you log out from here, your next log on will return you to the same spot so there's no hurry to see the whole collection in one visit. Enjoy!

Gallery

The Architecture of Pixels

A building that houses art should, of course, be artful. The Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, is a wonderful example of that. But... Virtual Reality is not REALITY. There’s no gravity for starters. You can float your building upside down or build it out of clouds. The sky is literally the limit. And that makes building impossible structures very, very tempting. The problem is that taken to extremes the art that a virtual gallery houses could find itself playing a distant second fiddle to its container.

Which brings us back to earth with a thud. The clear vision for Nuna is art. Design in this instance rides a tension between the 'impossible possible' and something more familiar to a visitor. At Nuna a carefully judged familiarity plays the dominant role out of these two principles.

That's not to say Nuna's designers haven't been inventive, playful and quirky. A virtual reality interface naturally lends itself to a level of quirkiness. Your avatar body has superpowers. You can fly like Superwoman. You can disappear like the Invisible Man. You can teleport like Spock. The list goes on. While your avatar won't gain any sustenance from a coffee or a glass of wine, there's still a cafe in the museum to sit and chat. There's an elevator to transport you between levels (you could fly, jump or teleport between floors, but, ironically, imposing real life limitations on your movement is somehow more satisfying.)

Avatars are not only able to see what’s in front of them, they can also "cam" (camera navigate) without physically moving. Sometimes you need to to this to find your bearings and sometimes it's just more efficient. Nuna's large open spaces are specifically designed with this ability in mind.

The gallery itself is necessarily large. At ground level is a sculpture park and the surrounding parklands. The parklands are quite beautiful and well worth exploring. They include cave systems with replicated prehistoric art.

The Penthouse (level 4, but who's counting?) is where the two Exhibition Galleries are found. These galleries feature contemporary exhibitions by professional artists. Exhibitions typically run for a month or more and have opening nights and other related special events. The benefit for an artist of exhibiting virtually is, of course, international exposure. 3RG has users and visitors from all over the globe.

Level 3 is dedicated to prehistoric, ancient and modern folk art. The prehistoric section is prefaced with a topological essay on human migration with an emphasis on the diaspora out of Africa by early homonids. Prehistoric art is mostly overlooked by art historians but that prejudice makes little sense. The minds that created these works were as sophisticated as our own and the works provide a context for all human art, through to the most contemporary work.

Level 2 includes Classicism, the Renaissance and Mannerism, the Impressionists, the Pre-raphaelites and the Hyperrealists. While this last group fits better chronologically in the contemporary section, they fall more easily to the eye set among other realist traditions.

Level 1 is dedicated to modernism and contemporary art. The works are laid out geographically and in the centre of the floor is the Gallery shop, on the balcony is the cafe. You can refer to our online map for navigation.

Art

The Animal Spirit

Human art pre-dates human language—it's one of our oldest practices. Art is intrinsic to our nature. Its products should be readily understood and accessed by anyone. Sadly, that is not the case with a lot of art in the modern era. There are complex reasons for this. Art has shifted away from documenting nature realistically; from toiling in the capricious service of patrons and theocrats; from functioning as decoration. The industrial age came on the heels of the Enlightenment and photography stepped up to the plate to challenge the need for painterly realism. Artists found more value in introspection, delving into psychology, metaphysics, politics and even interpreting the new reality of particle physics. The function of art was radically overhauled. Artists, working at the coal face understood this shift but the general public often lagged in seeing the necessity of sacrificing beauty on the alters of modernism and post-modernism. And that has led to a drawn out disconnect between the arts establishment and the public who still flock to the pre-20th century masters and largely avoid modern art.

A gallery isn’t a random collection of artworks. It’s a curation, a story telling. A work of art out of context can be daunting to someone not steeped in art history or art theory, but a properly curated gallery gives you context, it builds connective tissue and helps you to broaden your horizons. The story that Nuna sets out to tell is summed up by that single word: context. If you begin at the beginning, with the first symbols and animal portraits painted on the walls of caves, you see it. The human hand and mind working together, saying something that the artist wanted others to hear.

If you follow that thread into historic times, you see how that original artistry was transformed by culture but was rendered by the same sophisticated human hand, and with that realisation you can make sense of what came before and after. In classical times, a honing and veneration of skill led to an outpouring of monumental art. The renaissance revived that tradition after the middle ages, through which the grand tradition of western art was kept alive by the annotations of monks copying books in scriptoriums. The excess energy of the Renaissance inspired a reactionary energy that splintered into movements and rebellions and led to abstraction and stylisation in its myriad forms.

The spread of western cultural influence around the globe has infiltrated other cultural traditions and you can see a fusion of ideas and practice reinvigorating art in these cultures too.

And so we have returned to the beginning—the paintings of half-man, half-animal that spoke to shamanistic mythologies on the rock canvasses of our ancestors find a corollery in the modern depictions of the minotaur by Picasso. Both sets of works are laden with sexual energy, bristling with inscrutible intent, and represent the human hand in concert with its companion mind. Art has lost none of its power over our imaginations. The chance to view art as a tapestry, as afforded by Nuna, is a rare opportunity, not to be missed!

Prehistoric Painting

But is it Art?

There is no way to know with any certainty why our ancestors painted on cave ceilings tens of thousands of years ago. We simply don't have the knowledge to fully decipher their work. But what we do share with these painters is our intrinsic human nature. It weaves through all of our modern cultures and it came from somewhere. Perusing prehistoric cave paintings in Nuna Gallery-1 and understanding our own social drivers and interactions, we can imagine that they include a selection of motivations easily recognised today. The subject matter of many of the discovered cave paintings show animals, some of which were being actively hunted by our ancestors. It is easy to imagine wanting to capture being in the presence of a herd of buffalo on the move, or a family of lions on the attack. Countless pieces of contemporary art have been created to celebrate victories in battle. Success against other animals could be interpreted in much the same spirit.

Cave painting might also have served utilitarian purposes. Paintings of collections of hands (common across many cultures) may represent a form of census, a tallying of a population at a given time. There could even be a desire to leave a mark on the world that would live on after the people themselves have passed away. Hunting paintings, too, could serve utilitarian purposes. Are they an early form of recorded history? Or on a more practical level, could they be a way of comparing one season's hunt to another season's, possibly as a sort of competition with past hunters?

Animals in many of the cave paintings are portrayed in such accurate

detail (amazing when you consider they were painted from memory and the canvas and paints they were using) that they suggest the possibility some of the motivation behind the paintings may have been similar to the rationales behind Da Vinci's sketches of human and animal forms. Were they studies of the animal anatomy, of their power, spiritual force, grace and sophisticated design? Were they pre-literate lessons in how animals interact within a herd and between different species? They might have been a way for our ancestors to plan out new ways to hunt, to learn from other species and improve hunting efficiency.

But, if we are being honest with ourselves, it is difficult to look at these paintings and not recognise in them a desire to create something of one's own that expresses individuality and a personal view on the world. We can readily recognise them as art. The more we learn about our ancestors, the more we discover what we have in common with them. While modern Homo sapiens may have learned new ways to harvest death and new ways to control our surroundings, our core desires—our interest in merging individuality with community, our desire to celebrate and leave a personal trace daubed on the historical record, have remained constant. It is not difficult to find a connective thread between the art left behind by women and men at the start of our path towards civilisation and the art being created today.