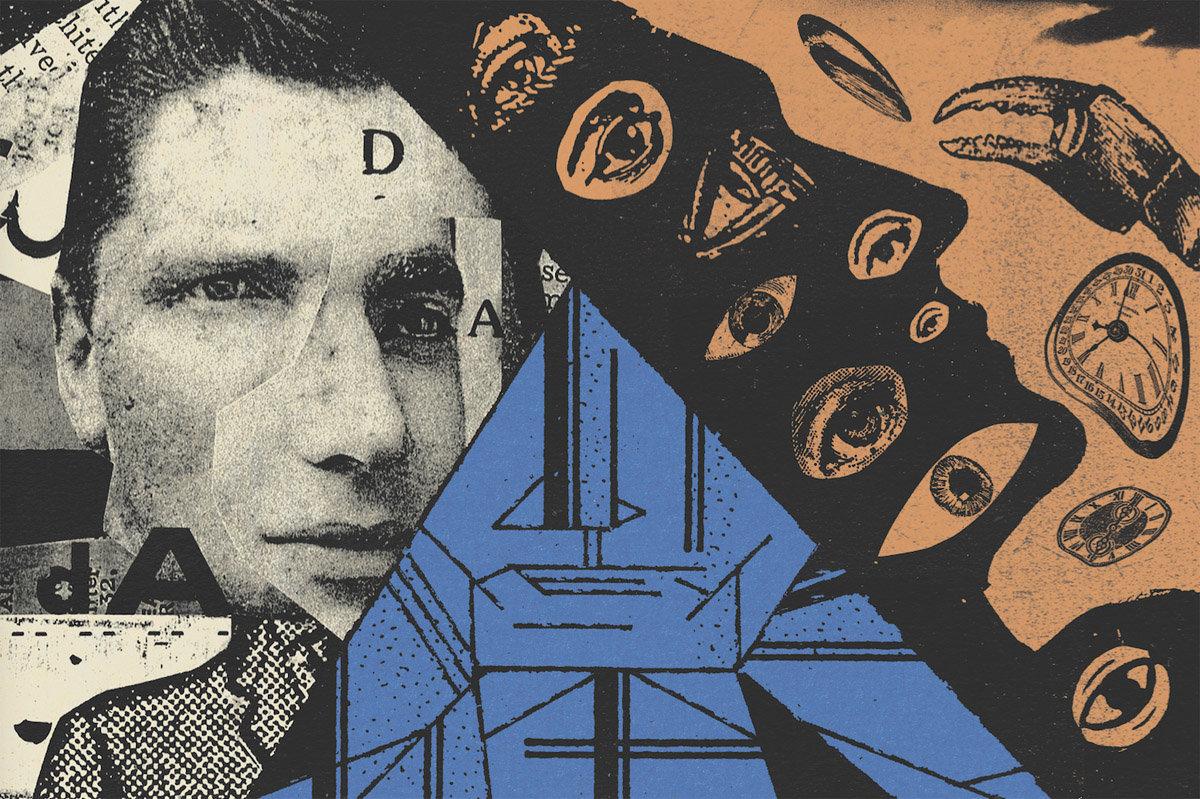

Dada

by Alia

Origins

Dada was the first conceptual art movement where the focus of the artists was not on crafting aesthetically pleasing objects but on making works that upended bourgeois sensibilities and that generated difficult questions about society, the role of the artist, and the purpose of art. It arose as a reaction to World War I and the nationalism that many thought had led to the war.

Dada embraced absurdity and dadaists were so intent on opposing all norms of bourgeois culture that the group was barely in favour of itself, stating "Dada is anti-Dada". Leading artists associated with it include Arp, Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia and Kurt Schwitters. Duchamp’s questioning of the fundamentals of Western art had a profoud subsequent influence on its development.

In this article tracing the origins of Dada, I'm going to take you on a Dada-esque journey. It starts in the 1890s with a diminutive Parisian, Alfred Jarry, who invented 'Pataphysics—the supremely ironic meta-metaphysics. This brief biography of Jarry is told with a nod or two to pataphor. A pataphor (Jarry's creation) is an extended metaphor that creates its own context (that which occurs when a lizard's tail has grown so long it breaks off and grows a new lizard!). All details of this history are accurate to the extent that any historical writing can be labelled accurate (i.e. not a work of fiction to the best knowledge of the author). At the end I'll supply a glossary of pataphysical terms to help you make sense of what you just read :)

The Copper Skiff: A Pataphysical Introduction to ‘Pataphysics

Alfred Jarry rode around the streets of Paris on a bicycle, his means of locomotion, carrying a green umbrella and two pistols. The pistols he fired to announce his arrival. His style was unique and remained so until Pablo Picasso, an admirer, acquired a pistol of Jarry’s for his own nocturnal peregrinations of Montmartre, where by day he was known at the Lapin Agile for buying his meals with a drawing. “Why don’t you ever sign your drawings Pablo?” asked the owner. “Because I only want to buy lunch, not your whole restaurant!”

Jarry, from the formative age of 17, had been a regular presence in the cafés of the Latin Quarter across the Seine, which snakes around the Ile de la Cité with a somnolent glide; hissing on masonry and slithering past the footings of the Pont au Double, its reflected lights a backdrop for the waiter whistling as a bar on Quai de Montebello approaches closing time. He notices a man of diminutive stature drinking from his own absinthe bottle at a street table and decides not to disturb him. It is Jarry returning from a play. In those cafés Jarry mingled with artists, philosophers and writers including a few Symbolists. Their theatrical productions were being noticed in the 1890s. Symbolism had pushed away from the Realism and Naturalism that were then the mainstays of French theatre. Authors like Stéphane Mallarmé, who befriended and mentored Jarry, and Alfred Vallette were choosing metaphysical poetry over stilted realism.

Jarry was excited by this stylistic revolution. He adapted their influence to create his own absurdist style of writing and, out of his inventions, Jarry did more than just create absurd characters—he adopted their mannerisms as his own. To a neighbour's obnoxious (or reasonable) complaint that Jarry’s pistols endangered her brood, he quipped, "If that should ever happen, ma-da-me, we should ourselves be happy to get new ones with you."

That talking style, the royal “we”, “ma-da-me”, announcing each syllable with nasal relish as though it were a new word, he acquired from Pere Ubu, the redoubtable King of Poland, who cut his own three teeth—one stone, one iron, one wood—teaching physics to Jarry under the pseudonym Felix Hébert. Imitating the speaking style of his teacher, who Jarry caricatured as a buffoon, completed the circle for Jarry. To adopt his speaking mannerisms, which were exaggerations of his own anyway and perhaps not Hébert’s at all, defied any reasonable explanation, and that was what counted. The mannerisms were really a form of symbolism, a metaphor for the teacher; by adopting them Jarry was growing a new lizard out of the abandoned tail.

In Ubu Roi, which premiered on 10 December 1896 at the Théâtre de l’OEuvre—a play that pre-empted the wonderful Theatre Absurd—the comically obese Ubu stepped onto the stage and announced “Merdre!” (a clinamen of Merde); its resemblance to the degenerate substance still close enough in French to create chaos in the audience. The booing, whistling and jeering lasted a full 15 minutes as an antimonious posse of depraved miscreants baited, cheered and applauded. Opening night was also closing night. Lugné-Poe, the theatre’s manager, shut down the play immediately due to the heat of the scandal and the rioting of the patrons, but Jarry had become famous literally overnight.

Spurred on by the success of this venture, Jarry refined his talking style further: his bicycle became ‘that which rolls”; the wind, “that which blows” and he always thereafter referred to himself with the collective noun, the absurdity of doing so dovetailing nicely with his other self-conscious eccentricities, much like the dovetailed jointing on the cabinet where he kept his revolvers, in a room too low-studded for anyone but Jarry to remain erect. Visitors crouching to shuffle around created a slapstick reality, which Jarry likely viewed as a syzygy of sorts. All this chaos was on account of his landlord’s anomalous caprice—dividing a larger apartment into two by way of a horizontal partition instead of the more sensible vertical. It should be a rule that every budding pataphysician inhabits an absurdity generator like that one to really get a feel for the subject matter.

Keenly aware that he cut no less comical a figure for his lack of elevation than the well-meaning Hébert did for his excess of girth, Jarry—in the modern coinage—chose to monetise his gift. He had already achieved dismissal from the army, into which he was drafted, by marching in a uniform too large for his stature, making a parodie of parades, another clinamen. They found medical grounds for his dismissal. The oversized uniform became one of his motifs, worn by the oversized Pere Ubu, no less, with whom, as mentioned, he had very little and a great deal in common. He wrote a set of plays featuring the vulgar Ubu, finding scant profit as he tried to reconcile the need for the involvement of the spectator with his “didactic misanthropy.” He both mimicked and mocked the Symbolists—and with that innovation his unique formula propelled theatre into a tango with absurdism, art towards Dada and scholarship into the age of post modernism. Not bad for a wee man on a bicycle.

While five novels and two collections of short stories were published during his lifetime, Jarry’s influence on the 20th century did not properly manifest until after his premature death from tuberculosis abetted by substance abuse—he squandered his modest inheritance developing a taste for libations and taking ether when he could not afford la fée verte. Exploits and Opinions of Dr. Faustroll, Pataphysician, the surreal work that launched Pataphysics on the sea that sits over Paris; and La Dragonne, were both published posthumously. Dr Faustroll died the year he was born at the age of 68. Jarry died in 1907 before he was born, his philosophical system of Pataphysics a posthumous love letter to the world, sealed in an absinth bottle, floating away from a copper skiff on the shimmering absolute, a golden sea above the city of lights.

Pataphysical Glossary

Clinamen: a swerve of atoms

Syzygy: an unexpected alignment

Antimony: a symmetry of opposites

Anomaly: an exception that disproves the rule

Absolute: a transcendent reality

Pataphor: a metaphor’s metareality

Source Material

Alastair Brotchie, Alfred Jarry: A Pataphysical Life. 2011

Maurice Marc LaBelle. Alfred Jarry, Nihilism and the Theater of the Absurd. 1980.

Martin Puchner. “Alfred Jarry.” The Norton Anthology of Drama. Vol. 2. 2009.