Pride & Prejudice

by Maya Tripitaka

Disconnect

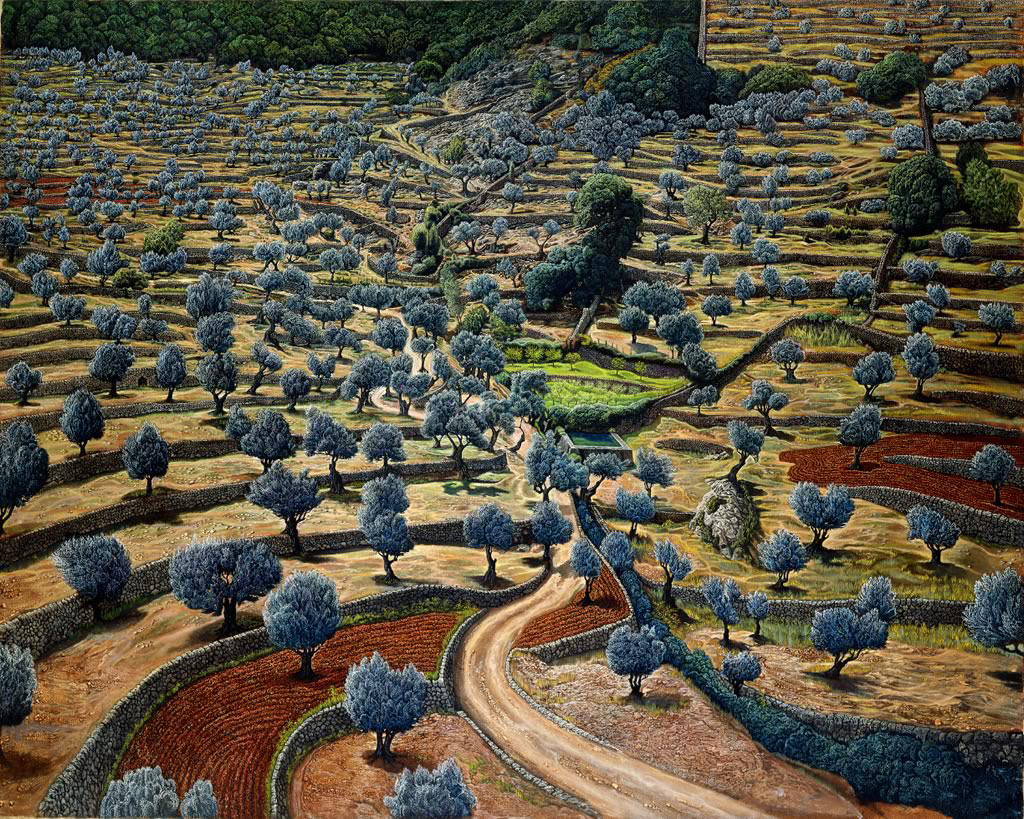

The images that tease you into this brief essay are by an artist you've never heard of, but you probably know his work. Abdul Mati Klarwein.

His artistic pedigree was immaculate. In the 1950s he went to Paris and studied painting with Fernand Léger. In St Tropez he received private tutelege from Ernst Fuchs. In New York Andy Warhol stated that Mati Klarwein was his "favourite painter". Mati Klarwein rubbed shoulders with the rich and famous. He dropped acid with Jimi Hendrix. He was commissioned to create new works for Jackie Kennedy, David Niven, Brigitte Bardot, Richard Gere, Leonard Bernstein and Michael Douglas, to name but a few. He was that rare thing, a celebrity among celebrities.

Where you may have seen his work though, is in connection with music. His paintings adorn seminal album covers from the 60s and 70s. He painted The Annunciation which is the cover of Santana's Abraxas. His works were used for the covers of Miles Davis' Bitches Brew and Live Evil albums. Musicians from that era clamoured for his art.

Despite all this attention, or perhaps because of it, his name doesn't appear in any history of 20th century art. He never worked with galleries or used any conventional forum within the well-defined boundaries of the world of art. He still remains (posthumously) shut out from the art establishment, unworthy of art criticism. This is not because he lacked originality as an artist. Long before Banksy developed his legendary distain for conventional practice, creating works and just leaving them randomly for others to profit from, Mati Klarwein had cultivated his own measured distain for his art product. He maintained the image was important and would happily paint replicas of his pieces if requested. He did not trouble himself to know what happened to any of the original work on completion. And like his admirer Warhol, Mati Klarwein accepted no boundary between his own work and the work of others, often buying paintings and working on them himself, unfussed if the same treatment befell his own paintings.

Nor was he a stranger to controversy (normally a catapult into the collective arts consciousness). In New York in 1964 he caused a commotion exhibiting his blasphemous Crucifixion. The painting depicts people cavorting in a garden of earthly delights where no sexual, racial or gender barriers exist. Public outrage to this work was such that he was even attacked by a man with an axe.

But, out of his broad spectrum of themes, his multi-ethnic, trippy, psychedelic musings did spark the imagination of an era of musicians who were experimenting with these same influences. And being popular with the wrong audience is something of a no-no in the serious world of art, a logic that aligns with the refrain "my enemy's friend is my enemy". In this case, the public, the “Great Unwashed” is the enemy. In telling contrast, the enormous enthusiasm within the arts establishment for an outsider like Banksy—a direct heir to the spiritual rebellion of Mati Klarwein—might have something to do with him being their discovery. It's, you know, ok for the public to follow—not so good when they lead. And that is the theme of this little exposition, the double-edged sword of art criticism.

Art criticism performs a vital function for art. It moves works, artists and events from short term to long term memory, etching it on the public record. Art is local and often ephemeral by nature so the critic disseminates the work in publications, books and other written media. They also evaluate art, which is an important function, prising out meaningful ideas in an ever shifting sea of relevance. So to preface my minor criticisms of critics, let me say that it is with an eye to the important role they fill, and against a backdrop of admiration for their craft.

It is a craft that requires passion for the subject matter. In light of this, professional impartiality is an impossible standard to expect or attain. The grasp that a critic has on art history is their best guide when evaluating new work, and the path that art has taken since the revolution of modernism looks from our present perch, necessary, inevitable, making it hard to imagine that other paths might lead anywhere worthwhile; while the paths that stay closest to their starting point (those that put realism and technique on a pedestal) are also the least interesting to the adventurer.

This is central to why hyperrealism has trouble being taken seriously by those who determine historical significance, and so too for Abdul Mati Klarwein, who was something of a pioneer of the movement, a bridge between surrealism and hyperrealism. It's also true that some exponents of the contemporary realism genre are as shallow as their pigments and they don't extend the language of art in any meaningful way, but the same charge can be levelled at many artists in other styles too. Some are astoundingly shallow and opportunistic style-plagiarists, but they avoid stigma by being on the right bus. There is a problem of prejudice at work.

The art establishment can’t afford to hold such a blinkered perspective. It’s fair to say that there are a lot of naive exponents of outsider art movements and a lot of misunderstandings among its practitioners. But outside the cloistered arts system is also where the next revolutionary gem is likely to arise. I point again at Banksy as a case in point.

Return to Essays